In 2023 I’ve read mainly after my daughters go to bed. I settle on the sofa with the monitor blinking at me, and try to resist the empty allure of social media. It's worked, mainly, partly because reading is and always has been so much richer in what it has given me than anything else. These are a few of my favourites, things that have lingered, things that have made me think, oh yes, this is how you do it.

I haven’t read his previous, Pulitzer prize winning All the Light We Cannot See, but I loved Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr. I found it so compelling, the interwoven storylines, the depth of the empathy for the characters. It’s made me think a lot about the effect of the short chapters, the way it drives your reading attention on, makes you think, oh go on then, just one more, keeps your interest and builds tension. A few other excellent novels I read this year used this form (perhaps influenced by our internet-addled attention spans?) and I’m trying to deconstruct it to see how it has that compelling, tense effect on the reader.

Science fiction and fantasy is in excellent health in the non- Anglophone literary sphere and I finally got my hands on The Liar’s Weave by Tashan Mehta, a writer from Mumbai. Beautifully written, about Indian astrology in a world where birth charts are everything, I’ve ordered Mehta’s next book which I am very much looking forward to.

Benjamin Myers does this kind of impressionistic thing with historical fiction that doesn’t try to mimic or reconstruct voices of the past but still puts you right there, in a way that ties you still to the present. Cuddy, his latest book about St Cuthbert, an Anglo Saxon saint who is buried under Durham Cathedral, is such a beautiful example.

The review called Birnam Wood by Eleonor Catton a ‘literary eco-thriller’ and I was like, oh come on, but it really was. There was fascinating, almost nineteenth century interiority to the characters with a really modern propulsion and complexity to the plot.

In Ascension by Martin MacInnes was recommended by someone I trust on social media and yet again, their taste has proven to be gold. Science fiction on the hugest, and yet also minutest scale, it has lingered with me for quite some time afterwards, pondering the ending, pondering the questions it raised.

I’m trying to read more short stories so I can understand the form better, and one of the best collections I read this year was Sing Your Sadness Deep by Laura Mauro. Recognisably from the same imagination but so varied and surprising, I found myself eager to start each new story which is unusual for me, as I find with short story collections I often flag in reading energy between each story and need something else on the go to swap out.

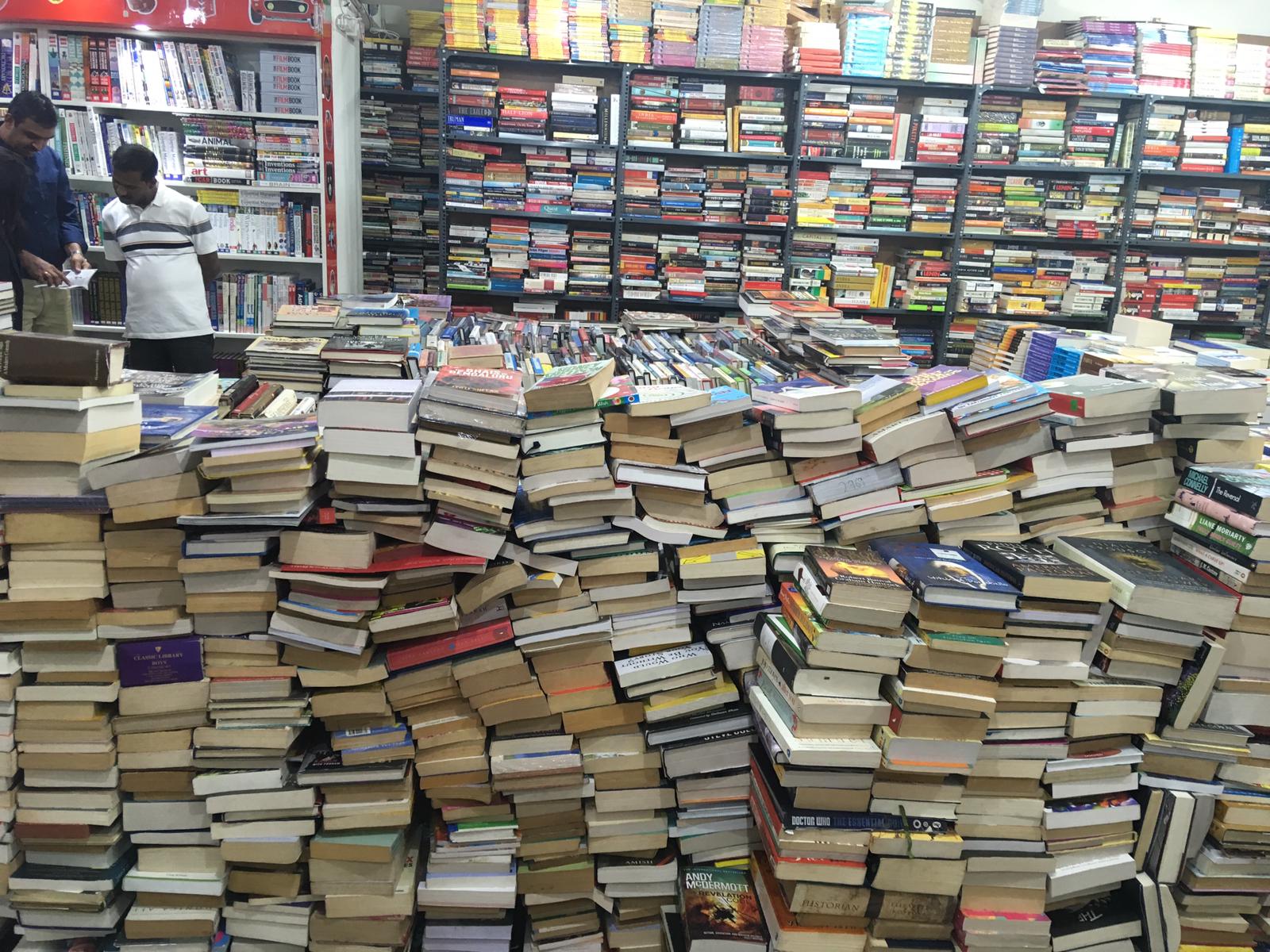

I picked up The Book of the Most Precious Substance by Sara Gran on a whim when I’d decided to treat myself to a new book on one of the rare times I actually went into a bookshop and it did not disappoint! A thriller about books and manuscripts and magic and sex, it was tense and so well plotted. Sara Gran is a writer I admire for the way she skates on genre borders, and I’ll be reading more of her next year.

I hardly ever re-read books as I’m usually in too much of a tizz trying to read new releases, books I’ve only just heard of but sound right up my street, or books I think I should be reading to complete my education. But this year I re-read two novels that I remember being stunned by before: Accordion Crimes by Annie Proulx (following an accordion made in Sicily on a boat to the US in the late nineteenth century which then makes it way through various different immigrant groups as the twentieth century progresses) and Fire and Hemlock (a loose retelling of Tam Lin) by my long time fave, Diana Wynne Jones. My other favourites of the year are all recently written and released but when you read older books you see quite clearly publishing fashions and trends and how they often don’t have much to do with what is ‘good’ literature or enjoyable narrative for the reader.